The last decade of purely clinical observation

|

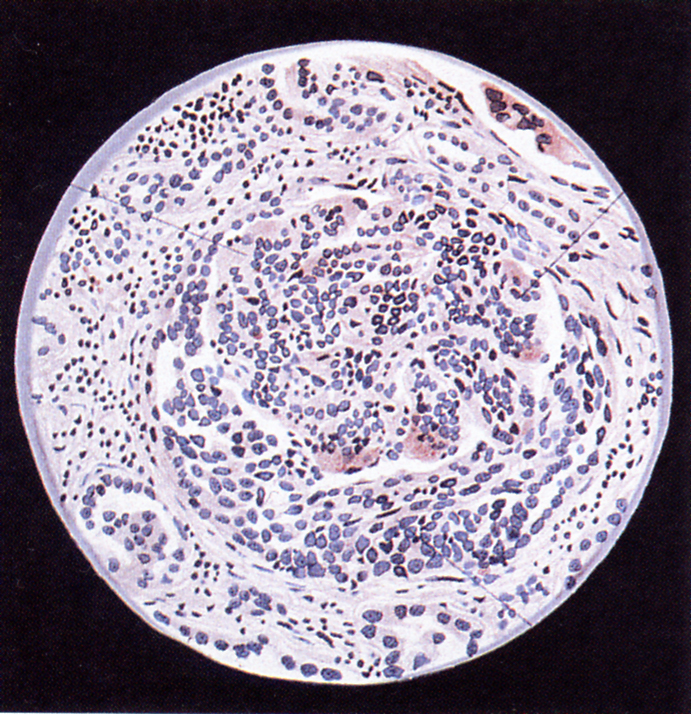

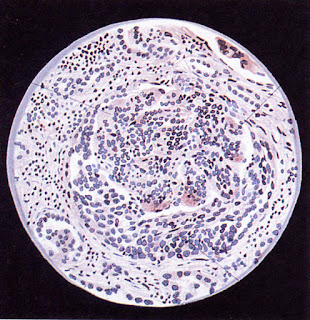

| Acute glomerulonephritis with crescent formation – Volhard and Fahr 1914 (one of the last renal pathology works with artwork rather than photographs) |

Arthur Ellis’s 1942 articles on Bright’s Disease summarised a truly impressive 20 year systematic recording of 600 patients with kidney disease at the London Hospital, followed up regularly, including autopsies.

Contemporaneously in London the crush syndrome (rhabdomyolysis) was being defined as a cause of renal failure, and the medical management of acute renal failure (acute kidney injury; AKI, ARF) was undergoing detailed refinement.

It was still a decade before the introduction of renal biopsies began to reveal the variety of kidney diseases; the first effective treatment for a kidney disease (steroids for minimal change disease) was discovered; haemodialysis was proved to be a viable acute treatment in the Korean War; and the first successful kidney transplants in identical twins. Some antibiotics were now becoming available, but there were no useful diuretics and very little effective treatment for hypertension.

Volhard and Fahr, clinician and pathologist, published a beautifully illustrated and influential book in 1914. They distinguished nephritis, nephrosis (‘degenerative’, thought to be tubular in origin), and chronic nephrosclerosis, but in doing so described many variants of glomerular pathology that we can still recognise, and distinguished the changes of malignant versus benign hypertension.

Ellis made mostly clinical distinctions, backed by pathology. He defined two types of nephritis:

Type 1 nephritis was simply acute glomerulonephritis, as so well described by Dickinson 50 years after Bright, and by many others. It was associated with haematuria, fluid retention and uraemia, and occured particularly following infections, in young patients who usually recovered.

He also recognised a subset of patients who did not completely recover, who had persisting haematuria and proteinuria, and often lost kidney function over years. 15% of their Bright’s Disease clinic patients had a clinical picture similar to this, but most did not recall an acute episode. Probably many of them had IgA nephropathy or other types of glomerulonephritis.

Type 2 nephritis was a condition with proteinuria but not haematuria, oedema, and usually a more insidious onset. A progressive course towards uraemia was common. Patients tended to be older. Under the microscope there was no inflammation, and glomerular signs were often subtle, but increasingly picked up by improved techniques.

Unlike Volhard and Fahr, Ellis assumed glomerular origin of proteinuria. Until only a short time before, nephrosis was widely thought to be a tubular disease, because on microscopy there was prominent vacuole formation in tubular cells, while glomeruli often looked normal by the techniques then available. Randerath’s beautiful and definitive experiments on salamanders proving the glomerular origin of proteinuria had been published in Germany just before the outbreak of war, but this does not seem to have been picked up by nephrologists beyond Germany at the time.

Ellis’s second article was about essential hypertension. High blood pressure not apparently caused by kidney disease had been identified by Mahomed and others at the end of the 1800s. It was divided into malignant hypertension, which caused renal failure, and benign hypertension, which he felt rarely led to serious kidney disease.

The third 1942 article commenced with The Vicious Circle in Chronic Bright’s Disease, and reflected on the relationship between renal hypertension and the progression of kidney disease. It also described chronic pyelonephritis, and summarised his proposed classification of Bright’s disease:

Nephritis

- Type 1

- Type 2

Essential hypertension

- Benign hypertension

- Malignant hypertension

Miscellaneous

- Acute focal nephritis

- Acute interstitial nephritis

- Toxaemia of pregnancy

- Mercurial nephrosis

- Amyloid nephrosis

- Chronic pyelonephritis

- Chronic nephritis of lead workers

Treatments and the future

Impressive though all Ellis’s data is, it is also apparent that there had been almost no change in ability to modify the outcome of these diseases since 50 years before or even longer – and the prognoses on offer were mostly gloomy.

The clinical principles broadly continued to hold, but the detail was to change dramatically over the next 25 years as individual diseases were distinguished by pathological appearances in life, and effective treatments began to become available.

Further reading

Richard Bright and the discovery of kidney disease (this blog)

50 years after Bright – Acute nephritis in 1875 (this blog)

The salamander proves the origin of proteinuria Nephrotic syndrome starts at the glomerulus (this blog)

Ellis AWM. 1942. Natural history of Bright’s disease. Clinical, histological, and experimental observations. Lancet 239:1-7, 34-38, 72-6. The text of his Croonian Lecture of 1941, which was not delivered because of ‘enemy action’. Unfortunately the War scattered notes and patients, and detailed information from this series, studied with Drs Horace Evans and Clifford Wilson, was never published.

Mallick NP, Short CD, Hunt LP. 1987. How far since Ellis? Nephron 46:113-24

Volhard F, Fahr T. 1914. Die Bright’sche Nierenkrankheit, Klinik, Pathologie und Atlas. Springer, Berlin.

Dickinson WH. 1867. Diseases of the Kidney and Urinary Derangements, Part 2 Albuminuria. Spottiswoode and Co., London.

Waldherr R, Ritz E. 1999. Edmund Randerath (1899-1961): experimental proof for the glomerular origin of proteinuria. Kidney Int 56:1591-6.

Two further accounts of acute glomerulonephrits:

Atenstaedt RL 2006. The medical response to trench nephritis in World War One. Kidney Int 70:635-40. An outbreak of acute nephritis in troops in the trenches in 1915 was badged Trench Nephritis. It sounds in retrospect (and to some at the time) to be just post-infectious acute glomerulonephritis.

Capon NB. 1926. Nephritis in childhood. Arch Dis Ch 1:141-65. Includes some detailed case histories, and accounts of the equivocal effect of renal decapsulation operations.