The first effective treatment for a kidney disease, 1950.

Dropsy is an ancient word (first recorded about 1290 AD) meaning oedema. Generalised oedema can be caused by heart or liver or kidney disease, or by malnutrition. In all of these it was a pretty bad sign in ancient medicine as it meant that the patient had advanced disease that was likely to kill them. By the early 1800s it was realised that some patients with dropsy had albumin in their urine.

|

| A woman with dropsy. From Albert JLM; Nosologie naturelle; ou, Les maladies du corps humain distribuees par familles. Paris: Carpelet, 1817. (US National Library of Medicine) |

Richard Bright, working at Guy’s Hospital in London, showed that kidney disease could cause dropsy. His studies were mostly post-mortem, and his patients had advanced renal failure, but he also realised that some patients had low levels of albumin in their blood because it was leaking from their kidneys. What we now call Glomerulonephritis was for over a century known as Bright’s Disease.

Only two years after Bright’s 1827 paper, Robert Christison in Edinburgh described patients with episodes of dropsy and albuminuria who got better without treatment and without developing ‘uraemia’, and others who had proteinuria not severe enough to cause dropsy. Accounts of relapsing dropsy in children followed soon after – the condition we now call minimal change disease. 1827 was 12 years after the battle of Waterloo and 22 after Trafalgar. Beethoven died that year, Charles Dickens began work in a law office aged 15, and Charles Darwin, aged 18, dropped his medical studies after two years for science.

German pathologist Friedrich von Muller introduced the term ‘Nephrosis’ in 1905, meaning a non-inflammatory kidney disease, to be distinguished from Nephritis, the inflammatory type of Bright’s disease. This distinction is still useful, but Nephrosis soon became used also to describe the clinical picture of dropsy with proteinuria. Between 1930 and the 1950s the term Nephrotic Syndrome largely replaced it.

Because of lipid deposits in tubules (‘lipoid nephrosis’), for a long time it was suspected that the tubules, rather than the glomeruli, were the source of the protein leak. The changes in the tubules are in response to the protein leak, not the cause of it, but the glomeruli only became widely accepted as the source of the leak in the 1940s.

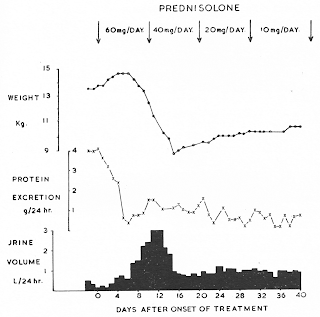

By 1949-50 the first exciting reports of a successful treatment for nephrotic syndrome were appearing, using the newly synthesised steroid hormones. This was probably the first effective treatment for any kidney disease. Very few other useful drugs were available. The mercurial diuretics, invented in the 1920s, were weak and toxic, and largely ineffective in nephrotic syndrome. Management consisted of salt restriction, with drainage of ascites by tube if abdominal swelling became intolerable, or by insertion of Southey’s tubes into the legs to drain massive oedema. Antibiotics were however reducing deaths from the severe infections which are common in nephrotic syndrome. Very high serum cholesterol was recognised to be a sign of the disease – plasma often white (lipaemic) from its fat content. A striking film from 1954 on Childhood Nephrosis ends on the upbeat note – ‘Childhood Nephrosis has by no means an invariably fatal prognosis … the outlook is heartening’, because with steroid treatment recovery could be expected in up to 50% of cases. The response rate in adults was much lower.

Today we have different treatments for over half a dozen common causes of the nephrotic syndrome, that we usually distinguish by renal biopsy. That technique was just developing in the 1950s, with many of the analytical techniques that we rely on coming still later.

Further information

Proteinuria – a bad thing since 400 BC (historyofnephrology, this blog)

Richard Bright and the discovery of kidney disease (historyofnephrology, this blog)

Cameron, JS Hick J. 2002. The origins and development of the concept of a ‘nephrotic syndrome’ Am J Nephrol 22:240-7.

de Wardener HE. 1958. The Kidney (1st ed.). London, Churchill. The classic nephrology text.

Cooke RE. 1954.

Nephrosis in chidren. Medicine Around the World, Vol 1 Film 4. Pfizer. Available from www.edina.ac.uk (with an academic login).

A version of this post was published in the Journal of Renal Nursing in September 2010.

4 responses to “Dropsy, nephrosis, nephrotic syndrome”

My great uncle died as a result of dropsy as a young child in the late 1890's. Could this be a result of an untreated strep infection?

That's just one of the possible kidney diseases that could do it. However dropsy just means being swollen up with fluied, and could alternatively be caused by liver or heart disease.

My grandma died of dropsy in 1960 is this likely to be passed to other family members

Almost certainly not going to be passed on, if she only developed it late on in life. It's likely to be too far away to get a certain cause now though.