Physiologists resolve an anatomical impasse, 1924

|

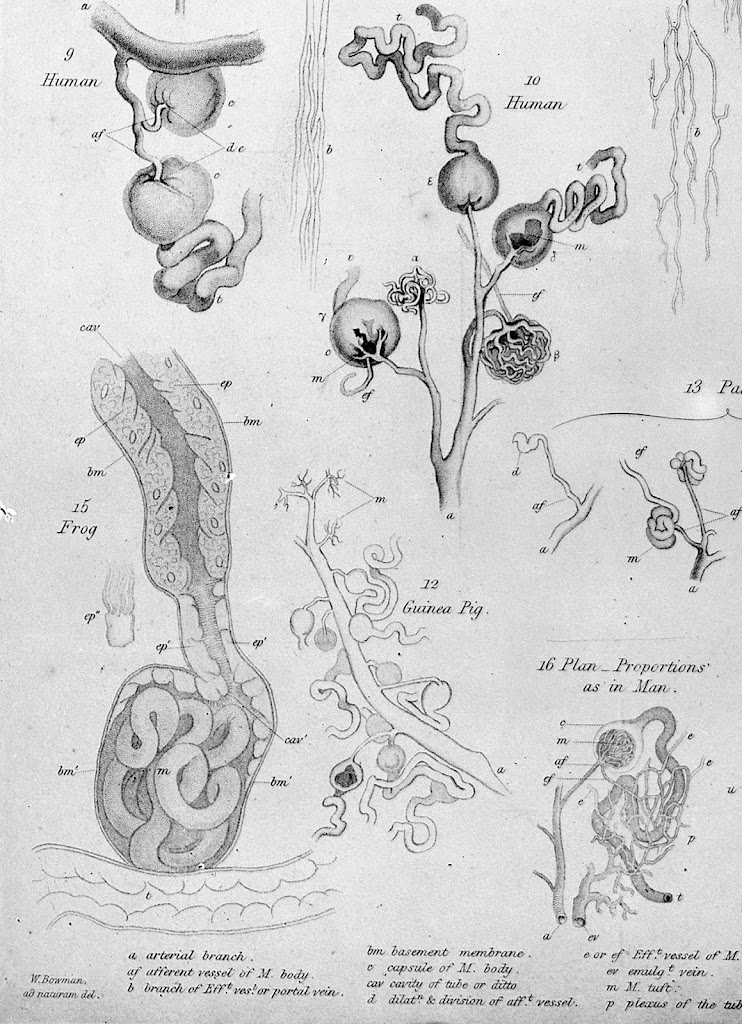

| Illustrations of Malpighian bodies, from Bowman 1842, Philosophical Transactions 132: 57-80 (p78). Wellcome Library (M0011305) – Creative Commons licence |

Malpighi spots glomeruli, 1666

The first microscopes emerged in the Netherlands in the 1600s, early discoveries being associated with Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in the Netherlands, Robert Hooke in England, and Marcello Malpighi in Italy. Malpighi examined biological samples, and recognised pulmonary capillaries that completed the connection between pulmonary arteries and veins which William Harvey had not been able to see when describing the circulation of the blood.

In 1666, the year of the Great Fire of London, he described ‘renal corpuscles’ (glomeruli) that became coloured on injection of black fluid and wine. He believed these linked blood vessels to the fibres (tubules/ collecting ducts) which had previously been recognised draining into the renal papillae by Lorenzo Bellini in 1662.

However the Dutch anatomist Frederick Ruysch, now remembered also for his bizarre dioramas involving children’s skeletons and body parts, came up with a competing hypothesis involving tubular secretion. For the next 260 years there was a lack of consensus over whether the glomerulus was essentially a filter, or whether the nephron was a secretory system.

Bowman describes glomeruli, but mistakes how they work, 1842

English surgeon/ anatomist William Bowman beautifully illustrated the structure of the glomerulus that we know in 1842 (Fig 1). Twenty years later, in Göttingen, Jakob Henle defined the convoluted path of the tubule from glomerulus to collecting ducts. However Bowman proposed that the process going on at the glomerulus was secretion of water, rather than filtration, and that other solutes were secreted from tubules.

Ludwig gets it right, 1842

Carl Ludwig had been undertaking similar investigations to Bowman, combining injection of vessels and microdissection with chemistry and physiological techniques, and also published his results in 1842. But he concluded that the process at the glomerulus was high volume, pressure-driven ultrafiltration, with the tubules reabsorbing large volumes of filtrate. He was right, but it was controversial. In 1874 German physiologist Rudolph Heidenhain published some misleading experimental observations, to which he later added that the volumes of blood flow and filtrate required to account for excretion of urea seemed implausible. Ludwig’s mechanism did not sway general opinion until it was favoured again in an influential book The Secretion of Urine (1917) by Scottish pharmacologist-physiologist Arthur Cushny.

Wearn and Richard finally prove it by micropuncture, 1924

80 years after Ludwig and Bowman, and stimulated by Cushny’s views, Joseph Wearn working in Alfred Richards’ lab at the University of Pennsylvania brilliantly adapted the new technique of micropuncture, using glass micropipettes drawn out to very fine points when heated, to take tiny samples of glomerular filtrate in frogs. In 1924 they published their findings that the upper end of the nephron contained a dilute filtrate that became more concentrated as it passed distally. As filtered it contained practically no protein, but it did include substances (chloride, glucose) found in blood but not in urine. These must have been reabsorbed as the fluid passed down the tubule.

|

| Nephron – Holly Fischer |

Renal physiology comes alive

The invention of micropuncture launched a revolution in detailed understanding of renal physiology, leading to explanation of the processes at each segment of the nephron.

It was a further 14 years before it was proven that the glomerulus was the source of proteinuria in nephrotic syndrome, (almost) finally establishing the respective roles of glomeruli versus tubules in both health and disease.

Further reading

Jamison RL 2014. Resolving an 80-yr-old controversy: the beginning of the modern era of renal physiology. Adv Physiol Educ 38: 286-95 (free full text). Outstanding, comprehensive account.

Diagram of the nephron. From Holly Fischer, © Regents of the University of Michigan – Creative Commons licence. [Source]