Indicates risk of renal failure and death

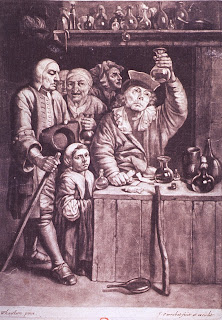

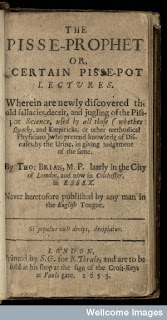

Hippocrates (400 B.C.) described bubbles on the surface of the urine as indicating kidney disease and a long illness. Inspection of the urine (uroscopy, Fig 1) was a major part of the art of the physician for many centuries, often going way beyond any evidence. A Dr Thomas Brian railed against this in a 1655 tract ‘The Pisse Prophet’:

Or certain Pisse-Pot lectures, wherein are newly discovered the old fallacies, deceit, and jugling of the piss-pot science, used by all those (whether quacks, and empiricks, or other methodical physicians) who pretend knowledg of diseases, by the urine. The analysis became more scientific only in the latter part of the 1700s, with the observation by that acidification or heating caused the urine of some patients with dropsy (oedema) to coagulate. This was an exciting time in science and medicine, but Stewart Cameron singles out Domenico Cotugno’s 1764 observations in a patient with nephrotic syndrome, and those of early clinical chemist William Cruickshank. Then in an outstanding set of clinical and autopsy observations Richard Bright conclusively demonstrated the association between proteinuria, dropsy and fatal kidney disease in 1827, and in doing so laid the ground for the specialty of nephrology. Glomerulonephritis was known as Bright’s Disease for over a century.

The analysis became more scientific only in the latter part of the 1700s, with the observation by that acidification or heating caused the urine of some patients with dropsy (oedema) to coagulate. This was an exciting time in science and medicine, but Stewart Cameron singles out Domenico Cotugno’s 1764 observations in a patient with nephrotic syndrome, and those of early clinical chemist William Cruickshank. Then in an outstanding set of clinical and autopsy observations Richard Bright conclusively demonstrated the association between proteinuria, dropsy and fatal kidney disease in 1827, and in doing so laid the ground for the specialty of nephrology. Glomerulonephritis was known as Bright’s Disease for over a century.

Proteinuria and mortality

Measuring proteinuria became a regular part of clinical assessment, and was subsequently taken up by insurance companies. At the first meeting of the Assurance Medical Society in 1894, the importance of measing albuminuria in assessing insurance risk was discussed. In 1912, increased mortality was described in 396 New york men who had been found to have proteinuria, but otherwise normal health, 10 years previously. Barringer also cited insurance company data from larger numbers of patients that suggested that mortality was more than doubled in individuals with a small amount of albuminuria and urinary casts. It is interesting in the light of later observations that there was not much evidence that the excess deaths were from renal failure, though this was probably easier to miss then.

In the last decade modern physicians have re-learned this message from a large number of epidemiological studies, which have shown that proteinuria is not only a renal risk factor, but also a powerful risk factor for cardiovascular events and death.

Proteinuria and kidney disease

The ability to undertake renal biopsies in the 1950s and to study them by immunofluorescence in the 1960s led to nephrologists spending the next 20 years largely studying the differences between different histological entities. However by the late 1970s it was realised that regardless of the underlying histology, greater proteinuria indicated greater long-term risk of renal failure.

The Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study (1994) showed again that higher levels of proteinuria were associated with faster decline in kidney function. However it also found that blood pressure control could dramatically reduce the rate of decline in patients with proteinuria. At the same time, Lewis’ equally famous trial of the ACE (angiotensin converting enzyme) inhibitor Captopril in diabetic nephropathy showed that it was significantly more protective than other drugs that lowered blood pressure to the same extent. And they lowered proteinuria too.

Since then studies in different diseases have confirmed that in patients with significant proteinuria (usually more than 1g/day or protein:creatinine ratio over 100 mg/mmol), a reduction in proteinuria brought about by ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) is associated with lower risk of progressive loss of kidney function. There are at least two ways to explain this but the argument is not yet resolved. Why proteinuria is associated with cardiovascular events is unknown, but it is not clear that proteinuria-lowering treatments is necessarily beneficial in patients with lower levels of proteinuria who do not have a primary renal diagnosis.

Testing for proteinuria today

Great efforts are currently going into searches for particular ‘biomarker’ molecules in urine that could be valuable in tracking inflammation, predicting transplant rejection, or diagnosing reversible/irreversible acute kidney injury. But just simple measurement of proteinuria remains an extremely valuable, cheap and simple test that is hard to beat.

The dry reagent dipsticks that we still use were invented by Alfred Free and Helen Free Murray, working at Miles Laboratories. Starting with dry chemistries in 1946, the first dipstick, Clinistix for glucose, was developed in 1956. More on the development of dipsticks.

Further info

Cameron JS. 2003. Milk or albumin? The history of proteinuria before Richard Bright. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18:1281-5

Barringer TB. 1912. The prognosis of albuminuria with or without casts. Arch Int Med 9: 657-64

A brief history of the Assurance Medical Society

Brian, T. 1655. The Pisse-Prophet. Published in London; from Wellcome Images

Cameron JS. 2005. The patient with proteinuria. In The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Nephrology, 3rd ed. OUP, Oxford.

Alfred Free and Helen Free Murray from the Chemical Heritage Foundation; also from historyofnephrology

A primer on proteinuria (edren Textbook)

This post, and many others from this series, are printed in sometimes shorter form in the Journal of Renal Nursing