Dustman before Duke?

|

| Title from the 1965 NBC documentary about dialysis in Seattle |

The first patient with end stage renal failure deliberately taken on for dialysis was Clyde Shields, who was started on treatment by Dr Belding Scribner in Seattle in 1960. A couple of years later several more patients were being kept alive in Seattle, and other centres were taking it seriously and attempting the same. By 1964, pressures were mounting on all units, so that it became increasingly necessary to turn patients away.

Efforts to reduce costs were introduced in attempts to treat more patients. Monitoring devices reduced the amount of supervision required. Dialysis became a treatment run without doctors by nurses and technicians. Subsequently, staffing was reduced further by getting patients to take on the work – even sending them home with machines to run the entire process themselves. These were truly empowered patients who became much more in control of their lives. But still dialysis was too expensive to take on all the potential patients, and different ways to manage this evolved.

In the UK, a common approach was simply to take on the next available patient if there was a space, while all others died – first come first served: ‘If the dustman comes before the duke, the dustman gets treated’ (Freda Ellis attributed this comment to Dr Frank Parsons in Leeds). So you just had to be lucky and develop end stage renal failure at the right time and place. Generally only young and otherwise fit patients were referred to renal units, although some did put in place official or unofficial age limits (such as age less than 40), or exclusion criteria such as diabetes or other comorbid conditions, or a simple test ‘can we get her/him back to work?’ or ‘can we get them onto home haemodialysis’.

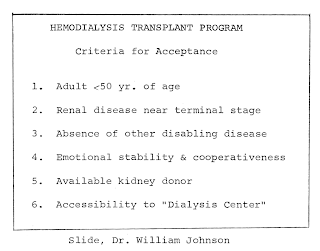

Other centres adopted more formal criteria and processes. In Seattle an age range of 18-45 was accepted at first, but soon a series of medical, social and psychological assessments led to consideration by the ‘Life and Death Committee’. This was made up of 7 anonymous individuals who were given the task of judging between the candidates put forward. This story is told in an outstanding NBC documentary Who Shall Live (YouTube) from 1965. It tells of the transforming effect of dialysis on those who could get it, the brutal consequences for those who didn’t, and describes the cost and political issues behind the policies. The essential medical criteria from the Mayo Clinic in 1964 are shown in the figure. The criteria in Seattle were identical except for the mention of a transplant donor, which was a common criterion in units where dialysis had been set up to support a developing transplant programme, which was common in these early years. The first diabetic patient was taken on in Seattle in 1969, nine years after Clyde Shields.

|

| Mayo clinic criteria in 1964. From 1964 meeting in Seattle |

It is tempting to think that these problems have gone away. However most of the world’s population lives in countries which still do not have the capacity to provide dialysis for all who need it. Here are the 2010 Tier 1 criteria for dialysis in the public sector in South Africa – they are remarkably similar:

Tier 1 – should receive dialysis in the public sector

- Age <50

- BMI <30

- HIV negative

- HepBsAg negative

- Suitable for transplantation

- No other negative factors

Others can be considered if facilities permit (Tier 2) if

- Home circumstances good (space, electricity, running water and sanitation)

- Well motivated and supported

- Able to afford transport

- HIV excellently controlled for 6 months

- HBV/HCV positivity without cirrhosis

- Non-smokers with no drug dependency or abuse

- No diabetes or other comorbid disease

Interestingly, the annual cost of dialysis in South Africa today is estimated at $10,000 per annum, which is exactly the same as the Seattle price in 1965. The estimated UK cost in 1965 was £2,000, equivalent to about $6,000 then. The 2010 price for centre-based haemodialysis in England was £22,000, $35,000.

Thanks to Dr Gavin Dreyer (Blantyre, Malawi), Prof Sarala Naicker (Johannesburg, South Africa), Prof Chris Blagg (Leeds, UK and Seattle, USA) and Prof John Feehally (Leicester, UK) for discussions and material for this article, which will also be published in the Journal of Renal Nursing

Further info

How South African doctors make life-and-death choices (BBC News link)

Moosa MR et al 2010. Guideline: Priority-setting approach in the selection of patients in the public sector with end-stage kidney failure for renal replacement therapy in the Western Cape Province.

Tomorrow’s World 1st edition 1965: view online from the BBC

Proceedings of the Working Conference on Chronic Dialysis (Seattle, December 1964)

Wellcome Witness to the History of Medicine 2009. History of dialysis in the UK (large pdf).

11 responses to “Who shall live? Patient selection for dialysis”

Prof Chris Blagg sends two valuable additional references: in 1987 John Darrah wrote a considered account of being on and chairing The Committee in Seattle from 1962-1970 (The Committee, Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs 33:791-3).

In 1998 Prof Blagg himself wrote about the development of ethical concepts in dialysis in Seattle in the 1960s (Nephrology 4:235-8), at the same time describing the financial and political environment and giving a detailed account of the criteria for acceptance. An article in Life in 1962 brought the new idea of dialysis, and how to select patients to save, right into the public eye.

Do you know where I can get a copy of Who Shall Live? Thanks.

I have tried to ask NBC but no response so far

Hi There, I am in Cape Town South Africa and my mother was one of the unfortunate patients not meeting the criteria. She died a slow and painful death exactly two years ago. I am on this site because I am conducting research for an awareness campaign I wish to launch in August 2011. My mom's birthday is in August and I really want to make a difference with her in mind. The worst thing I had to witness was the knowing look on her face, the silent tears she cried and hur tug of war with life and death. If you have any contacts, leads, links to other sites please mail me at contact@nazsalie.co.za……….Any help appreciated.

The Renal Support Network has copies of the documentary – contact lori@rsnhope.org

See reply below!

That's great to hear, it really deserves to be seen widely

A correction – Sister Freda Ellis was quoting Dr. Frank Parsons – not Victor Parsons

Of course – apologies, and corrected above.

The Who Shall Live NBC documentary has now been posted on YouTube https://youtu.be/FMay5zw1loA

The Who Shall Live NBC documentary has now been posted on YouTube: youtu.be/FMay5zw1loA